Roy Sakuma: Laughter, Love and Hope

By Jodie Chiemi Ching

His name is synonymous with the ukulele, an instrument that transformed his life at age 16 leading him to a career as Hawaii’s foremost ukulele teacher, an award-winning record producer, and founder of the first ukulele festival which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2020. Whether you’re talking story with the 74-year-old Sansei from the Makiki area of Honolulu, or listening to him play the ukulele, it’s hard not to be affected by Roy Sakuma’s love for people and music.

However, Sakuma’s life journey started with more emotional and mental trauma than many of us will ever know. His inspiring story is rooted in the experiences of a young Roy who suffered from bullying, low self-esteem and confusion growing up in a home with untreated mental illness. Sakuma believes these heartbreaking stories stay in him so that they can have a positive impact on other people’s lives which continues to ripple out beyond the shores of Oahu, his island home.

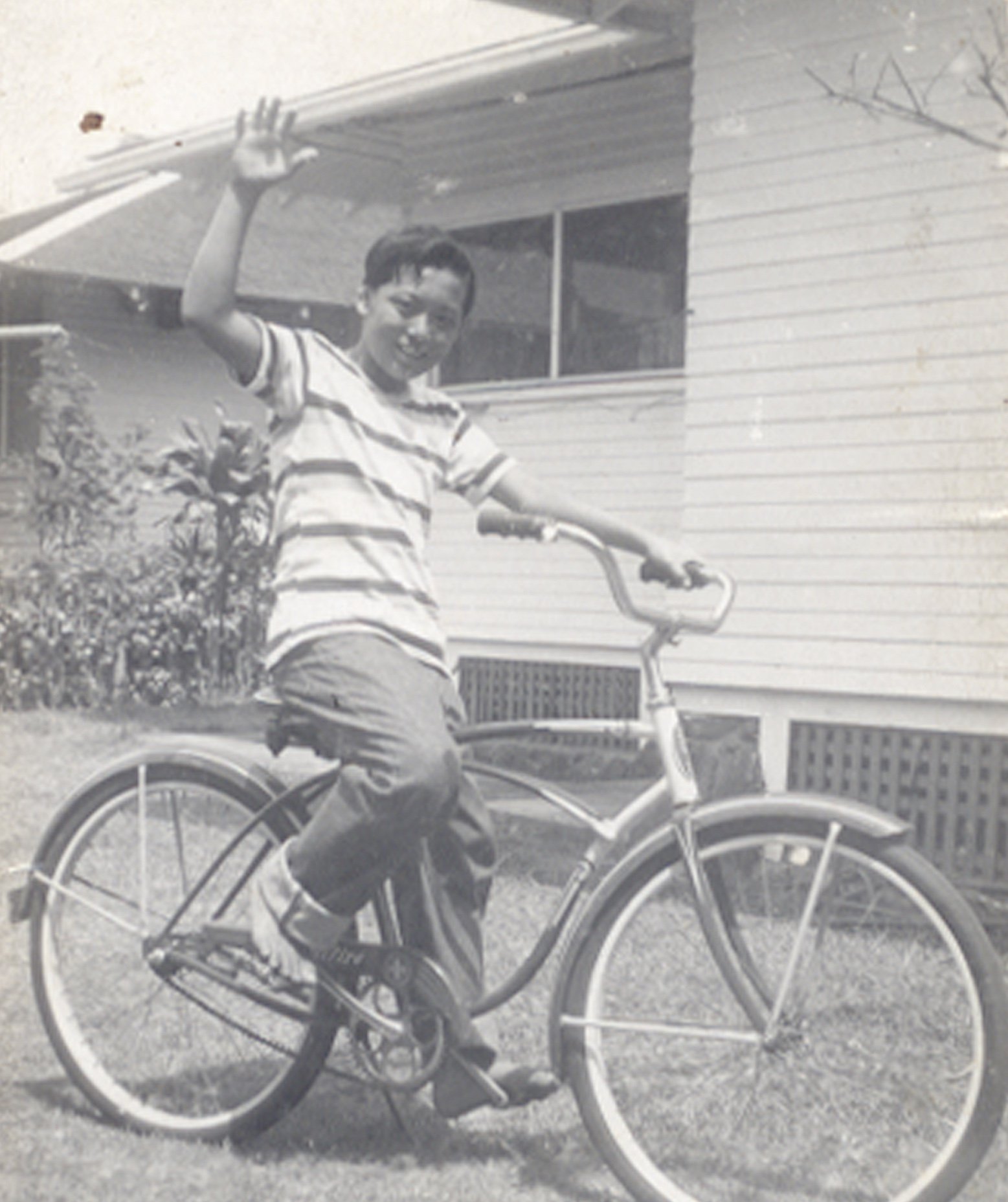

Roy Sakuma was born in Honolulu in 1947 to Warren and Ayako Sakuma. His grandparents were from Hiroshima. He was enrolled in public schools, Queen Kaahumanu Elementary School and Robert Louie Stevenson Intermediate, but from the age of five barely attended his classes. It continued that way at Theodore Roosevelt High School in Makiki and he dropped out before he could finish the 10th grade. One day the principal called him in and said, “Roy, one of us has to go, and it’s not me.” That was the end of his schooling.

In a 2008 interview on PBS Hawaii’s “Long Story Short” with Leslie Wilcox, Sakuma explained why he cut out of school so much:

“I went through a lot of pain, and I didn’t realize it until years later when I was born, my mother was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. So I didn’t have a normal childhood. And growing up, it was difficult, because I couldn’t distinguish what was right and what was wrong; and so I developed a lot of misconceptions in life. My father didn’t have the support to take my mother to get help because during that time it was shameful. And as the years went by, it only got worse, because my brother also had a mental breakdown. I was nine years old and he tried to attack me with a kitchen knife. I couldn’t sleep. I was afraid he would harm me so I would wander out till 2 o’clock in the morning until I knew my brother was asleep.

“So our home was filled with a lot of difficulties,” he said. “I have ear deformity and as a child, endured teasing from other kids. The teasing was hurtful and a struggle for me to relate to the kids my age. I felt like the weird-looking kid. My mom was incapable of consoling me. And I think for those reasons, I was always cutting out of school. I mean, who cuts out of kindergarten?”

But Sakuma said that his school problems forced him to look for a job, landing one as a stock boy at Wilder Food Center. He was a hard and fast worker and well-liked by bosses.

“I poured my heart into whatever I was doing,” he said. “It was a way of dealing with my pain of insecurity, from wondering why I have all these struggles while everyone around seemed so normal.”

Family History of Benevolence

When Sakuma was 21, he applied for a job with the City and County of Honolulu, Parks and Recreation department. With his limited education, he qualified to be a groundskeeper at the Kapiolani Regional Park located at the end of Waikiki just below the slopes of Diamond Head. A park director, Young Suk Ko, told Sakuma, “Did you know that your grandfather owned a lot of land in Hawaii?” This surprised Sakuma but he recalled that his dad would collect rent from houses on Liliha Street, across from Mayor Wright Housing, and then, on Date Street.

Sakuma began to connect the dots regarding the land owned by his family. “In the back of [an] apartment building, there was this huge Japanese school,” he recalled. “I was polishing my car one day in the school parking lot, and a man came up and yelled, ‘Get outta here! This is private property!’ And just [at that moment] my father comes walking in because my father owned the building in front. And the man bowed to my father. My father introduced me as his son. And the man said, ‘You can stay here.’”

It turns out Sakuma’s grandfather donated the land to the Japanese school. “What my grandfather had done was, donated or sold the land to Japanese immigrants and helped them get a start in Hawaii,” Sakuma said. “And then when my father passed away, all these elderly Japanese people would come and pay their respects at his funeral and I had no idea who they were. …

They said, ‘Your father helped us so much.’ I am thankful to hear of these stories of the generosity of giving many, many people from Japan after the war a way to get a good start.

“My father had the same generous heart as my grandfather.”

Sakuma looked up to his father as a brave, intelligent, and benevolent man. Warren Sakuma was a Nisei soldier who served in the Military Intelligence Service. “His job was to question prisoners,” he said. “When the war ended, one of the prisoners gave my father his sword as a thank you for his compassionate treatment. I have that sword as a memory.”

Sakuma said he was inspired by his father’s ability to see past the dark war and embrace the beauty of Iwo Jima – stories shared in the book, “The Battle of Iwo Jima.”

“These stories I will always treasure,” he said. “I’m proud of my dad, he was a good man.”

Roy’s Musical Journey—Hooked on Herb “Ohta-San” Ohta

2008 – Ohta-San & Roy Sakuma

When asked about his musical journey, Sakuma’s face lit up. He recalled that his house was very old with a large porch filled with children every day. They played card games like trumps, hearts, and sometimes blackjack and poker. When they got bored, they would head to the street to play football.

“A lot of kids could play the ukulele,” he said. “They tried to teach me when I was about 12. They said, ‘Here Roy, hold this chord and strum.’ I had no sense of rhythm, so they said, ‘Nah, nah, nah, you cannot play the ukulele.’ So I tried again when I was 14. My best friend could play ‘Yellow Bird’ so he tried to teach me but he gave up.”

Sakuma’s sister, Faye, played the ukulele. She tried to teach Sakuma to strum with rhythm by banging a beat with a pot. But he couldn’t catch the beat and Faye told him to just stick to sports.

Then, when he was 16, Sakuma heard Herb “Ohta-San” Ohta’s hit song “Sushi” on the radio. Ohta-San is recognized as the world’s most diverse and masterful ukulele player. Sakuma fell in love with the song “Sushi” and waited every day to listen to it on the radio. That was the turning point of his life.

One day, while Sakuma’s best friend was looking in the newspaper for a job, he stumbled on an announcement that would catalyze his life’s calling: Ohta-San was giving ukulele lessons. So Sakuma made the call and was soon set to attend his first ukulele lesson with the famous musician. Learning to play the ukulele made him happy and took away a lot of the pain.

“For the first lesson, he taught me how to read music,” Sakuma recalled. “Then he taught me to play rhythm and strum. I had no concept of rhythm. I couldn’t even dance.”

But Sakuma had a talent that he would only recognize later in life: a photographic memory. Ohta-San would show Sakuma the music sheet, take the sheet away and found that he could memorize the chords and notes to the song very quickly.

“Once I play something, I see the relationship and I got it in my head! That really helped me learn ukulele really well,” Sakuma explained. “Finally, he would give me the most difficult songs to play, things that don’t even make sense and I’d come back and play it for him. So after 18 months, he told me, ‘Roy, I’ve taught you everything I know. You’ve learned what it took me five years to learn. There’s nothing else for me to teach you, so you can go on your own.’” Sakuma was sad that his ukulele lessons had ended. Until a year later.

A Brand New Challenge

After about a year had passed, Sakuma received a phone call from Ohta-San asking for his help. Sakuma said, “Oh yeah, sure. What do I have to do?”

Ohta-San replied, “I’m teaching class on Saturday morning. You want to come and help me?” Sakuma went to the class and his job was to tune the ukuleles. After the class finished, Ohta-San asked Sakuma how he liked it.

“Oh, I enjoyed it!” said Sakuma.

“Okay, I am leaving for Japan to do a concert tour. Teach my classes for two weeks,” Ohta-San said. With no teaching experience, Sakuma was in shock. But his mentor assured him and told him to, “Just do what I do.”

The 18-year-old Sakuma practiced at home for hours every day talking to the walls; pretending the walls were his students. He fumbled with his words at first and eventually thought of questions they might ask him and practiced his responses. “I probably practiced 30 hours that week,” Sakuma said, laughing.

“When I went in front of those adults to teach that following Saturday,” recalled Sakuma, “I was comfortable! I wasn’t even nervous.”

When Ohta-San returned to Hawaii from Japan, he asked Sakuma how the teaching went. Sakuma said that he loved teaching. So Ohta-San told his young protégé take over the classes since his career as a performer was thriving.

That’s how Sakuma discovered that his true calling was not in performing but in teaching. With Ohta-San’s blessing, Roy and Kathy opened the Roy Sakuma Ukulele School, which has been at its current Kaimuki location since 1974 in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Ohta-San wasn’t the only one Sakuma credits for his success.

A Girl Named Kathy

In his early 20s, Sakuma met Kathy, and they dated very slowly. “She was the first girl I ever felt something for,” said Sakuma, “I didn’t know what to do. And I wanted to hold her hand but I was afraid. So I figured it out. I took her to the Punahou Carnival because I knew that the carnival would be so packed with people, you gotta hold hands otherwise you’re gonna get lost in the crowd. It was our eighth date and I held her hand!”

With a huge smile, Sakuma shared another favorite story about Kathy, who eventually became his wife. “When I met Kathy, I wanted to show her my mentor Ohta-San. I said, ‘Do you like ukulele?’

“’She said, ‘Hmmm, not really.’” But Sakuma offered to take her to Ohta-San’s show and she accepted the invitation.

When Sakuma and Kathy arrived at the venue there was a long line to get in. To impress Kathy, he reserved a table front and center by the stage. “So Ohta-San plays on stage, his first set. And I am so proud to be there with Kathy next to me,” said Sakuma, all smiles. “After the set, here comes Ohta-San walking up to us, and I am so nervous to introduce Kathy. He walks right up to HER, doesn’t even say hi to me. He looks at Kathy and said, ‘What you doing here?’

“‘Oh, I’m here with Roy,’ [Kathy said].

“’How’s your mom and dad?’ asked Ohta-San.

“And I am thinking,” Sakuma said with a big laugh, “What in the world is going on over here?” It turned out that Kathy and Ohta-San are cousins.

“Oh my gosh! She knew how much I admired him. I think she probably didn’t want me to know because it [might] influence my feelings for her,” said Sakuma said, still laughing.

After a year and a half of dating, Sakuma knew he would love Kathy for life and proposed. She said yes. Sakuma went home a happy man until he woke up the next morning.

“In the morning, when I woke up, I started to think about it and I started crying and I knew I had to let [Kathy] go,” Sakuma said. “So we went out, and I told her to please listen. And she just listened. I gave her a hundred reasons to walk away from me. I told her my whole life, all the things I did. I told her all the misconceptions I have of life, the fears I have, the things that I see that are not normal, but it consumes my life. And I told her to leave me and find a better man.

After Sakuma opened his soul to Kathy, she told him, “I never saw it as your weakness. I see it as your strengths.”

“And THIS is what love is,“ Sakuma said. “Love is healing. Until this day, I still feel love entering. It’s like this never-ending love just filling me up all the time. And it’s to that love that I share and give to children. … That’s what I pray every morning, is to be filled with love so I can give this love to others.”

Instead of harboring resentful feelings of his horrific childhood, Sakuma believes all of this happened to him for a reason – to help others heal.

Healing Others, One Ukulele at a Time

Through all his career success, Sakuma would’ve been happy to keep his painful childhood buried and in the past. But there had been many wasted years as a youth trying to find himself and he realized those years would not be wasted if others could benefit by learning from his experiences.

Pre-pandemic, Sakuma’s renewed purpose was to help children heal by speaking to them from his heart. He tirelessly volunteered his time visiting schools and speaking to school children, including at-risk students, sharing candidly about his life experiences regarding bullying, suicide prevention, dealing with insecurity, and encouraging children to find healing so they may find the strength and courage within themselves to make better and wiser choices to live full lives.

Roy shares his message of love and forgiveness and teaches the children a song he composed in 1970, “I Am What I Am” –a song of accepting and being ourselves.

I am what I am.

I’ll be what I’ll be.

Look, can’t you see,

That it’s me, all of me.

He shares the meaning of the song about accepting and being ourselves and that our greatest weaknesses are there to help us find inner strength. Roy receives hundreds of letters from children thanking him for sharing his story. The children’s stories touch and tug at his heart. “It’s okay who I am” and “I’m special” and “It’s okay to be who I am, and I don’t have to be who I’m not.” Powerful words. This song is meant for all to share with everybody.

Following the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan, Sakuma and his wife visited the area. “We visited shelters and brought 200 ukuleles and chocolate candy,” Sakuma said. “People lost their homes, everything.”

Sakuma asked them, “May I hug you? For those of you who would like a hug, please come up and practically everyone came up.”

The pastor in Fukushima who served as a translator for Sakuma told him, “I know you came here to teach ukulele. But there is a bigger reason why you are here.”

Roy Sakuma Ukulele Studios

Kathy Sakuma reminds her husband about his gifts. “You get them to smile,” she tells him. “You get them to laugh. They know that you care.” And that is the philosophy the instructors at Roy Sakuma Ukulele Studios hold dear to their hearts.

Hoku 2004 – Roy and Noel Okimoto: Best Jazz

1995 – Kaau Crater Boys

“Our teaching staff is all former students,” Kathy said. “Roy Sakuma Ukulele Studios stands on the shoulders of our staff of instructors, the generations of instructors over four decades who have left their mark on countless of students and their families. Our staff understands that the connection we make to our student’s hearts is what it’s all about. At the end of the day, that’s what they take away with them. It’s much more than just teaching the ukulele.”

Roy Sakuma Productions record label has produced well-known groups and is recognized with Na Hoku Hanohano awards: Ohta-San, Kaau Crater Boys, Lyle Ritz, Noel Okimoto, Herb Ohta, Jr., and more. Ukulele virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro is a former student of Roy Sakuma Ukulele Studios, actively participates in Ukulele Festival Hawaii and serves on the Board of Directors of Ukulele Festival Hawaii.

History of Ukulele Festival Hawaii

Sakuma was a groundskeeper at Kapiolani Park and he would dream of showcasing the ukulele’s versatility and virtuosity with a free concert in the park. This was at a time when the ukulele was thought of as a toy and everyone wanted to learn to play the guitar. With the help and guidance of his friend Moroni Medeiros, his dream came true. In 1971, Roy put on the first ukulele festival at Kapiolani Park with the support of sponsors, local musicians, volunteers, friends including the Hawaii International Ukulele Club and the City & County of Honolulu.

Today, the annual Ukulele Festival at Kapiolani Park in Waikiki is now a summer tradition. It is the largest ukulele festival of its kind in the world with crowds of thousands, internationally known musicians, celebrities, an ukulele orchestra of hundreds from ages five to 85, and ukulele players from around the world celebrating the diverse sound produced from the four-stringed wooden instrument whose predecessor came to Hawaii from Portugal more than a century ago.

In 2004, Roy and Kathy established a non-profit organization, Ukulele Festival Hawaii, to continue their life’s work of promoting and building public awareness of the ukulele as an instrument of virtuosity and to ensure that the annual ukulele festivals remain a free event.

2013 – Ukulele FestivalHawai, Kapiolani Park

Ukulele Festival Hawaii’s Mission Statement is “to bring laughter, love and hope to children and adults of Hawaii and the world through the music of the ukulele.”

In 2020, the Ukulele Festival Hawaii celebrated its 50th Anniversary with a television documentary hosted by Roy Sakuma and Jake Shimabukuro. And in 2021, the 51st Annual Ukulele Festival Hawaii event was globally livestreamed virtually and hosted by Sakuma, Shimabukuro and Herb Ohta, Jr.