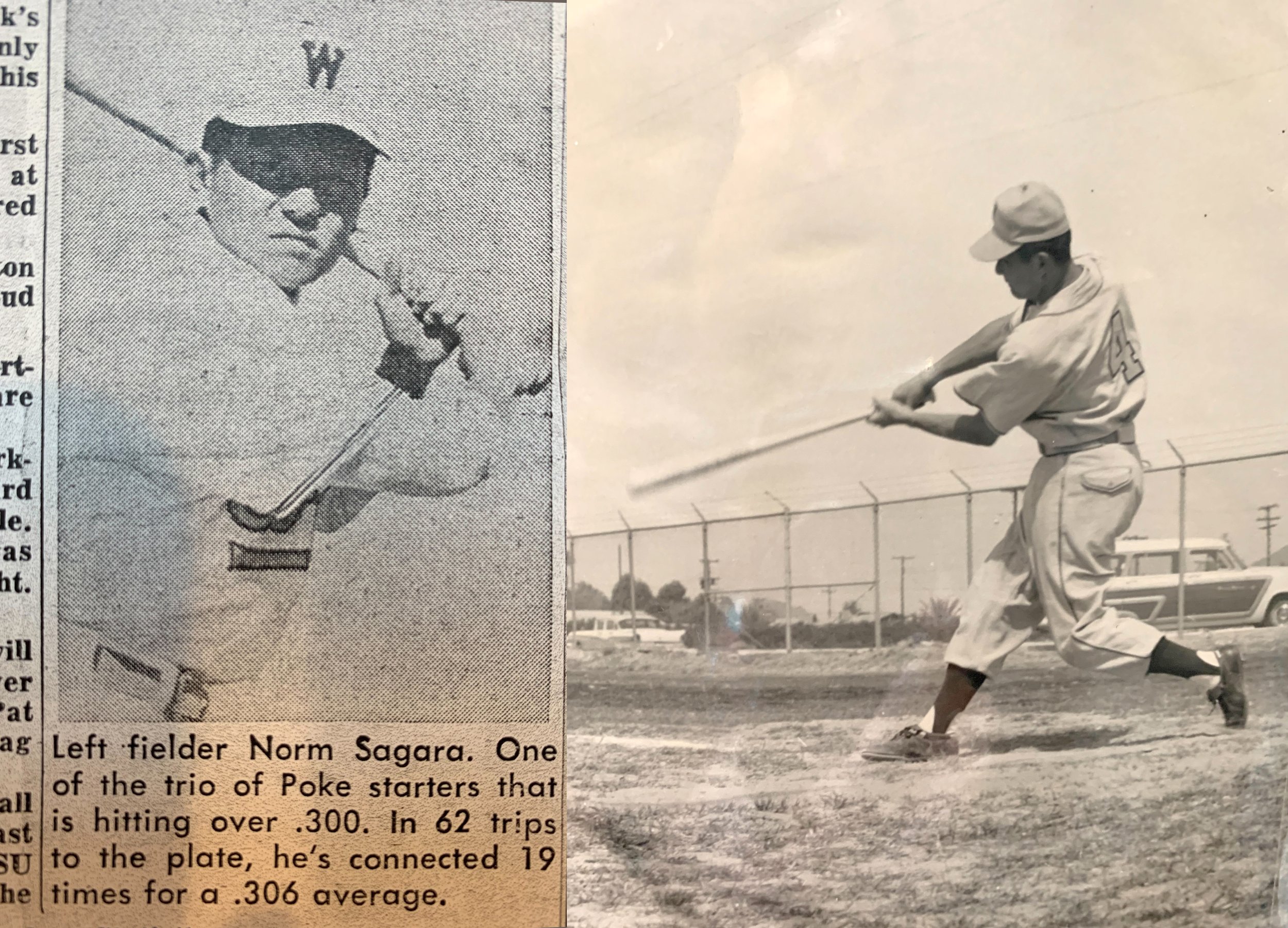

Norm played for the University of Wyoming - 1958-59 season

Norman Sagara:

Baseballer with a Samurai Spirit

By ellen endo

The Sagara family’s immigration story began in Japan in the late 19th century as Japan’s isolationism and feudalism were coming to an end, and the Meiji era opened the door to more modern, industrialized nation state.

Norm (front row on the left) with his siblings

With the fall of feudal Japan, the samurai class became obsolete. Lack of work meant they would inevitably face poverty. Tomotaro Sagara made the difficult decision in 1917 to leave his hometown of Izumi and travel to the United States. Putting his eldest son in charge, Tomotaro ventured to America with his second son, Hachisaburo, 15. The two came through Angel Island and soon landed in Seattle where they found work tending to fruit orchards.

Years later, Hachisaburo returned briefly to Japan where he met and married Yukiye, the daughter of a school administrator in Izumi. The couple was among the last to legally immigrate to the U.S. from Japan prior to passage of the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924.

When Norman Masaru was born in 1935, the Sagaras were living in Sacramento. Norman was their fifth child.

The family moved to Southern California where, encouraged by a friend, Hachisaburo set his sights on raising chickens and starting an egg ranch. They were living in Norwalk, and Hachisaburo had just finished building two brooder houses when World War II broke out.

Norman was only six years old, but Sunday morning, Dec. 7th, remains a vivid memory. “We were listening to the radio (when) we heard that Pearl Harbor was under attack by the Japanese. I knew my parents would be eager to hear about things like that, so I quickly ran over to the chicken ranch where they were working. They were stunned because they understood, more than I did, the consequences of what that could bring forth.”

Norman went to school the next day, only to find that the friends he used to play with, were no longer his friends.

In March 1942, two FBI agents arrived at the Sagara home and told them they were to report to Santa Anita Assembly Center in Arcadia. The family of seven left their home and business behind and were soon living in horse stalls. A few months later, they were on a train headed for Rohwer, Arkansas, where one of 10 concentration camps had been built to house about 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, citizens and non-citizens alike.

“Shikataganai (it can’t be helped),” his parents would say. “It must have been humiliating for my dad,” Norm says. “He convinced his wife to stay (in America) and raise a family, and you get this, you get treated like a second-class citizen.”

Norm (eight) at Rohwer, Arkansas Relocation Center

Norman went through the second, third, and fourth grades while confined at Rohwer. In the fall of 1944, the heads of the households were given an opportunity to leave Rohwer. Recognizing that the camp was not a good experience for children, Hachisaburo applied for the work release program in Michigan where he was hired by a greenhouse. Soon, the family was able to join him.

For 10-year-old Norman, it was a chance to play his favorite sport: baseball. He joined a summer league there. “I was a pitcher but became an outfielder. I was a better outfielder,” Norm admits. The team went on to win the city championship.

About four years after World War II was over, the Sagaras were driving back to Norwalk from Michigan.

They stopped at a motel in Wyoming. The motel clerk asked them about their nationality. When he learned they were Japanese, he said, “Sorry, we can’t take you.”

Whether it was the samurai spirit instilled in him by his father or the competitiveness he learned from having two older brothers, Norman grew to become a young man filled with determination.

Sagara, now 86, recalls “I started at Excelsior High School in Norwalk. I knew they had a baseball team there, (but) I didn’t make it. I didn’t make the cut and became disappointed.”

The family moved to Anaheim. Rather than try out for the Anaheim Union High School baseball team, Norman went to work helping his mom, who had two acres of strawberries that needed tending.

Back Row: Norm’s brothers, Peter and Frank; father Hachisaburo; Norm. Front Row: sister Grace; mother Yukiye; sister Alice.

Upon graduating from high school, he came across a new opportunity to pursue his penchant for sports. “I learned that a good friend of mine had tried out for the Fullerton College team, so I tried out even though I didn’t have any high school (baseball) experience. Fortunately, I made the team and played that first year, that first season.”

“After the first year, baseball-wise I was fine. But academics wasn’t my strong suit. The Korean War had just ended, but they still had Selective Service.

“I was not doing much in college. I had to grow a little bit, so I wrote to the Draft Board and said, ‘I’m ready to go.’ Sure enough, the next month (September 1956), I was drafted into the U.S. Army.” He served two years in Germany.

Sagara returned to Fullerton College where he made the All-Conference team, was hitting .390, and named team MVP. He received interest from several colleges, including Fresno State and legendary USC baseball coach, Rod Dedeaux. Through his Fullerton College coach’s contacts, Sagara was offered a full-ride baseball scholarship by the University of Wyoming, which was just coming off a trip to the 1956 College World Series. The full ride offer came with the chance for Sagara to make it to the College World Series, sight unseen. He became the starting center fielder for the Cowboys, earned All Skyline Conference honors both seasons, and finished the final two years of his college eligibility, earning a degree in education, with a minor in science.

Norm and Louise-Wedding Day 1962

After graduating from the University of Wyoming, Sagara got his first teaching job at Walter Reed Junior High School in the San Fernando Valley. He married his wife, Louise, and in 1965 took a job teaching science at Artesia High School, moving his family to Orange County. Along with teaching, coaching seemed like the next logical step for Sagara. He coached baseball and football at Artesia High School, serving as head coach of the varsity baseball team for six years.

“I decided that coaching wasn’t for me. So much confusion, rules, and regulations.”

Instead, Sagara completed his master’s degree and earned his administrative credentials. He became a guidance counselor and a teacher at Cerritos High School, later moving into a part-time counseling position in the school district before retiring after almost 50 years as an educator.

1993 Senior Softball World Series

Over the years, the desire to play baseball never left him.

In the late 50’s, Sagara joined the Li’l Tokyo Giants, a legendary, league-leading adult team based in Los Angeles. He played Sunday ball for the Giants for four or five summers as part of the Nisei Athletic Union, playing against teams from Northern and Southern California. These included teams from Lodi, San Jose, Fresno, San Francisco, and the Friends of Richard (FOR).

Sometime in the 1990s, Sagara heard the call to play ball again. He signed up for a softball team made up predominantly of older Caucasian players, retired from teaching, and continued to play until he was 70. To those who marvel at his ability to continue playing at that age, he says, “There are players who are 85 years old and still playing.”

Today, Sagara revels in being a father and grandfather. He has four daughters—Carolyn, Susan, Barbara, and Kathryn—and seven grandchildren. Several of his grandchildren have been actively involved in Division I college-level sports, such as lacrosse and baseball.

2017 Sagara Family

Norm teaching his grandson Chad how to swing the bat

One grandson, Chad Castillo, appears to have inherited his grandfather’s affinity for baseball. Sagara taught Chad to bat left-handed, just as his own father, Hachisaburo had done, which may have contributed to their success at the college level. Castillo has been a college all-star and is currently being eyed by the majors.