KILAUEA: THE POWER OF NATURE

Bruce Omori's Passion for Photographing “This Incredible Living and Breathing Planet”

By Patsy Y. Iwasaki, PhD.

“As a kid, what fascinated me the most about photography was that it would freeze a moment in time.”

To find his calling and passion, Bruce Omori — acclaimed professional Hawai‘i nature-and-landscape photographer — reawakened the small kid days of his youth immersed in the nature of Hawai‘i island. “I remember taking photos of plants and animals, flowers, everything; we also had birds,” recalls Omori who received his first camera when he was 9 or 10 years old from his maternal grandfather Minoru Takehiro.

“As a kid, what fascinated me the most about photography was that it would freeze a moment in time. I thought it was like magic you know? I couldn’t understand how it did that. That characteristic of photography being able to freeze a moment in time. I just loved that idea,” marveled Omori.

In fact, the talented mechanical-designer turned-award-winning photographer became so skilled at arresting time, he’s received international recognition and accolades. Omori’s striking photograph “Volcanic Vortices,” that captured multiple waterspouts that were generated when lava from Kïlauea volcano poured into the ocean, won the top honor in the “Power of Nature” category of the prestigious Windland Smith Rice International Awards in 2013. It was displayed at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History’s annual exhibition and according to a media release, it was selected from almost 20,000 submissions from photographers in 46 countries.

Volcanic Vortices

“On an early morning shoot at the Waikupanaha ocean entry… it created a huge escape of steam, and as it rose, multiple vortices began spinning off of the huge plume. A vortex or two is a pretty rare sight, but when one after another kept forming, my fumbling with the lenses turned into a panicked rush to switch my telephoto to wide angle lens to capture this awesome scene of seven vortices in a row,” said Omori as he described that moment in time he was successfully able to capture.

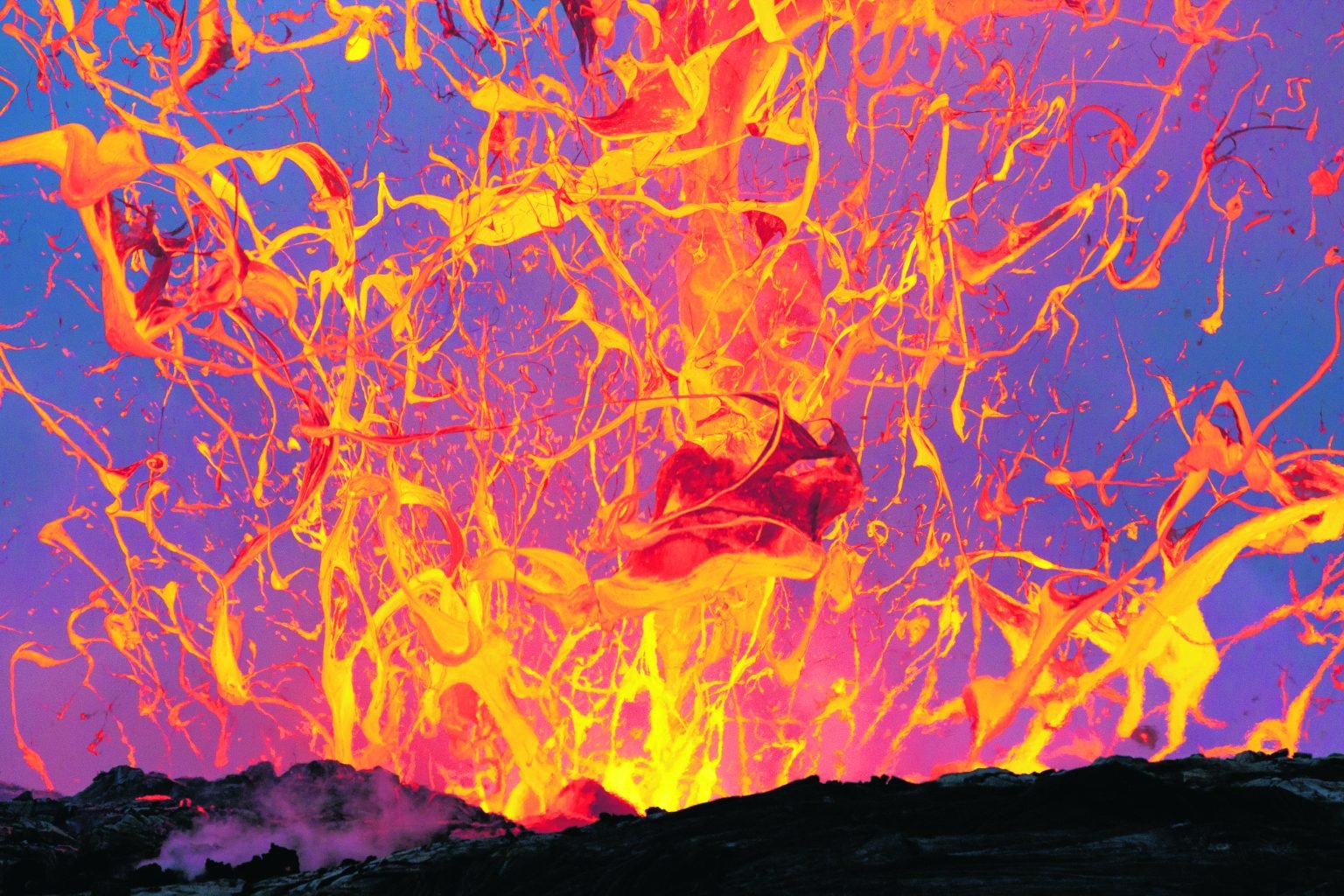

Two years later, in 2015, Omori was presented with the Windland Smith Rice International Art in Nature Award for “Ribbons in the Sky,” an abstract shot of lava exploding in the air, that he said balanced nicely against the early morning light, again coming in ahead of thousands of submissions and displayed at the Smithsonian.

“Lava bubbles are definitely one of my favorite aspects of volcanic activity, as its infrequent and unpredictable nature make it difficult, yet exhilarating to shoot,” said Omori in a Nov. 16, 2015 “Big Island Now” article. “The bursts are so spontaneous, there is no way to plan for a precise composition, and this 50-to-60-foot-wide bubble was no exception. I’m just so thoroughly blessed to have the opportunity to witness, let alone photograph, this incredible living and breathing planet we dwell on.”

Ribbons in the Sky

Omori delights in taking abstract images of eruptions and lava flows. “I love abstracts, so a lot of my work is abstract-related. At first I never thought about that; that these would be popular,” shared Omori about his love of lava formations, whether they are pyrotechnic explosions, such as the award-winning “Ribbons in the Sky;” “Earth Angel,” a lava formation that looks like a wing; “The Tongue;” a flow that looks like the appendage; the popular “Bleeding Heart;” or interesting design flows with descriptive names such as “Blue Velvet,” “Crusty Creases,” “Lucky Charms,” “Webbed,” “Wrinkly Wrinkles,” and “Fractured.”

“There are a lot of people who actually love abstracts. I always try to change it up. I’ve got, you know, thousands of images that haven’t been seen and every now and then I’ll go into my archives and pull up a new one that I think is different enough to catch attention. So I’ve been slowly taking these guys out, bringing them out,” said Omori, who sometimes “retires” other images. “You know, in my growth as a photographer, some of the images that I took early on, I don’t know if I got tired of it or maybe the way I shot it is kind of an embarrassment, but some of them I’ve taken out of circulation,” said the 1977 Hilo High School graduate with his trademark modesty and soft-spoken demeanor.

Terra Not so Firma

How does he come up with the interesting names? “Some come to me instantly and naturally, because they are so obvious, like ‘The Tongue’ looks like a ‘tongue,’ and “Volcanic Vortices” are a bunch of ‘vortices.’ But there’s others I sit with for a while, and others that are named because of the situation when I took the shot, ” said Omori. “Terra Not so Firma,” is a breathtaking photo of a stream of lava flowing dramatically into the ocean.

“I was standing on an outcropping of land that was brand new, it wasn’t there the day before. It was so unstable that it could liquefy in a second. This building of new land, it’s a continuous process. A delta will extend out to the sea and then collapse; and it will continue to build out and collapse, build out and collapse. It’s a slow process and is very dynamic,” explains Omori about how he captured that image.

“I’m standing on the roof of a lava tube and I can see the lava exiting the tube that is just a couple of feet in front of my tripod. It’s extremely hot. My shoes are melting and my tripod legs are melting. I could only stand there for just a couple of seconds before I had to get off because it was so hot. I couldn’t breathe,” shares Omori in his always amiable, quiet, gentle manner as if he were discussing the weather and not describing a life-and-death moment.

“I was able to fire off maybe two or three frames then I had to run off to catch my breath, ran back to shoot a couple more and then I had to leave the area. It was getting scary,” said Omori who added that he’s ruined dozens of shoes and a lot of tripod legs in his quest to capture these moments.

These stunning snapshots in time, as well as many other volcanic and natural images, are on display and for purchase at the photographer’s Extreme Exposure Fine Art Gallery in central Downtown Hilo, a gallery and store Omori renovated and opened in 2010, along with other artists’ work, including glass, wood and other media. “Extreme Exposure” was already the name of Omori’s online site (extremeexposure. com) that has featured his work since 2002. He settled on the name because of his history with surfers on the North Shore of O‘ahu in the early 2000s.

Moonlit Spendor

“I became friends with Brazilian professional big wave surfer Joao Jabour and he had a couple of boys who we called ‘groms,’ a slang word for young surfers. They were young kids and they were really good surfers and wanted to be sponsored by either a clothing manufacturer or surfboard maker because the equipment can be expensive, and I wanted to give them exposure. And exposure can also mean capturing a frame,” explains Omori about wanting to help the boys. “Surfing is an extreme sport, but I also wanted to give them ‘extreme exposure.’ I thought the double meaning fit well for what I was shooting then. Little did I know that the name would continue to fit what I shot in the future,” said Omori who primarily shoots lava flows and lavascapes now. “That’s our hottest item. I think everyone who visits the Big Island has an expectation of seeing lava.” Like many businesses, Omori had to shut down the gallery and store during most of 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but now that travel restrictions have eased, business is picking up.

His unique perspective on volcanic activity and lava flows also includes images from the 2018 Kïlauea summit eruption and subsequent Halema‘uma‘u crater collapse, and the 2018 lower Puna eruption. Before the 2018 eruption on May 3, a series of earthquakes emptied the lava lake, that had existed for almost a decade in Halema‘uma‘u crater, into the Lower East Rift Zone. The crater collapsed, sank 1600 feet, and its diameter doubled to about one mile across.

In 2019 USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory scientists observed water accumulating on the bottom of the crater because it was below the water table. The pool grew to form a lake that was approximately 160-feet deep. At first the pond was a light blue, turquoise color, but due to the changing mineral content, the lake turned orange and was the first water lake to be recorded at Kïlauea in modern times.

Halema‘uma‘u

Omori captured the riveting view of the massive cone-shaped crater with its orange-colored lake with an image titled “Halema‘uma‘u 2020” from a helicopter. The image is indeed a moment frozen in time because the water vaporized when Kïlauea erupted in December 2020 and lava flowed once more into the crater. Within a week of its creation, a 600-foot deep lava lake had replaced the historic water lake. This helicopter chartered photo-shooting day was exceptionally productive, but that doesn’t always happen.

“Every time I go out, I shoot hundreds, or maybe thousands of images. Sometimes, you know, I’ll have a few in there that are good. Other times, there’s nothing that is good enough. So it varies upon the activity and conditions. If conditions are difficult, you know, if there’s a lot of heat rising, then thermal distortion will blur the imagery and the images become useless, Omori said, about the difficulty of working with Mother Nature or Madame Pele.

“‘I‘iwi” or a Scarlett Hawaiian honeycreeper

In addition to volcano, landscape and lavascape images, Omori also focuses on native Hawaiian birds such as the Hawaiian hawk, the ‘io, the short-eared owl, the pueo, and the Hawaiian honeycreeper, the ‘i‘iwi. “I love our endemic species. As I grew older, I began to learn about how our climate is changing. Climate change has a lot to do with why the Hawaiian honeycreepers are in peril now. Global warming causes the spread of avian malaria because of the increased range of mosquitoes,” said Omori who credits his love of nature and his desire to create awareness about climate change, to his maternal grandparents Minoru and Misao Takehiro. He and his two sisters, Claire and Sheri, spent a lot of time at their home in Honomu and he fondly recalls helping them in their vegetable garden, their aquariums with freshwater fish, and bonding with his grandfather over their shared interest in photography.

Omori’s maternal great-grandparents, Kitaro and Tsuta Takehiro, immigrated to Hawai‘i from Hiroshima Prefecture, and his paternal great-grandparents, Kamehachi and Sode Omori, from Kumamoto Prefecture. Both sets of great-grandparents came to Hawai‘i to work on the sugar cane plantations. “I love plants and animals and science. I always had this fascination with the world we lived in,” said Omori, who believes the educational aspect is the most important part of his work. He also feels he had a typical country upbringing in Hawai‘i: spending a lot of time outdoors in nature, fishing with his father, growing a vegetable garden, and raising pets like dogs, cats, and a rabbit.

Although Omoriʻs award-winning photography journey seems straight forward, it was actually a circuitous path, one that involved graduating from the drafting program at Hawai‘i Community College, moving to O‘ahu, and working for 25 years as a successful mechanical designer/owner at a private engineering firm in Honolulu. He and his wife Sheryl were pretty settled on O‘ahu; they had purchased a home in Mililani and were raising their son Justin and daughter Rachel.

“I love plants and animals and science. I always had this fascination with the world we lived in.”

However, their lives began to change in 1998 when Omori’s father, Nobuyoshi, was terminally ill with colon and liver cancer and his mother, Takaye, showed signs of Alzheimer’s disease. During his father’s illness and after he passed away, a few months later, Omori began flying to Hilo often to help his mother with chores and errands, eventually tag teaming once-a-month visits with his sister Claire Suzuki who lives in Kona. His other sister Sheri Pierson currently lives in Colorado and visited and helped when she could. “Every other week, my mom had company,” said Omori of the arrangement. However, her condition worsened and she needed more help so Omori started flying back to Hilo every other week.

Omori and his wife Sheryl discussed the possibility of moving to Hilo to help care for his mother. When the time came, the Omoris sold their home in Mililani and moved to Hawai‘i island in 2004. Omori kept his mechanical designer job at the engineering firm, often putting in an average of 60 hours a week and more during tough deadlines. In order to keep up with his responsibilities and duties, Omori began to commute daily to Honolulu, and to catch up with his work, he began staying and working through the night for one night, then two, then three.

It wasn’t long before the inter-island commute and workload started to affect his health and Omori began experiencing an irregular heartbeat and chest pains. Although he took many tests, there was nothing wrong with his heart. His doctor thought the stress of the job, commuting and working through the night was taxing his body too much and that the stress would end up killing him.

“I took some time off while on O‘ahu and went to the beach to reflect upon everything. That‘s when I began to realize that because of my job, I missed out on a lot of my kids’ growing up. My relationship with my wife, my kids; they were all compromised because of my long hours. And it began to affect my health. That’s when I finally saw the light. I needed to do something. I really struggled with that decision since my career was my identity. I think Sheryl wanted me to leave long before that, but it took me getting to that point to realize I needed to make a change,” shared Omori humbly and honestly about being burned out. For the sake of his health, Omori made the hard decision to leave the firm.

Since he was still experiencing chest pains, Omori didn’t look for another job right away, but took a much-needed break and sought refreshment in the natural environment of Hawai‘i island with his camera. “I never stopped taking photos, I took photos for work, and of the children. I just didn’t have much time to dabble in my photography.” Now he had the time. “I would go out and shoot our Native Hawaiian honeycreepers and plants and surfers,” said Omori, immersing himself in nature’s healing surroundings. His body began to recover and the chest pains went away.

Edge of Creation

“It saved my life,” believes Omori and freelance work began to come in. “I posted photos on an online forum and some editors looked at my work and they liked it. I started shooting for a couple of magazines and a wire service, and surfers would buy my photos and surf magazines too. I even did some weddings. I started to earn a little bit of money,” shared Omori, whose incredible photo of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea at sunset taken from an airplane was selected as a mural in ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center’s permanent exhibit in Hilo. He also finally bought a Canon EOS-1 series camera for himself. One thing led to another and he began shooting lava in 2008 when Kïlauea erupted and the lava flow was moving through Kalapana.

If you can believe it, the photographer who is now internationally known for his lavascape images was initially afraid of the volcano. “I’m asthmatic and allergic to sulfur.” What?! “I avoided the volcano at all costs,” said Omori, who was never able to exit the bus when on school field trips to the Volcano area. “My mom instructed the teachers and told them I needed to stay in the air-conditioned bus because of my asthma. I remember watching my classmates run around outside, jumping over cracks, digging into the cinder, picking up rocks — and I couldn’t do any of that. I had to do my assignments while stuck on the bus. They could touch, feel and smell things and I couldn’t.

“I was really afraid,” said Omori. “But because of that obsession, I wanted to go. So I took my respirator and my inhaler with me and went to Kalapana to watch the lava cross Highway 130. I smelled the sulfur in the air and felt the heat.”

“I became obsessed with lava. Maybe because I couldn’t experience it myself. So I would get my fill from looking at photos, reading books, and watching documentaries,” said Omori about his predicament. Flash forward to 2008 when a friend suggested they shoot lava.

“I was really afraid,” said Omori. “But because of that obsession, I wanted to go. So I took my respirator and my inhaler with me and went to Kalapana to watch the lava cross Highway 130. I smelled the sulfur in the air and felt the heat.”

“I started wheezing, but I had my inhaler,” said Omori, who quickly learned how to mitigate the risk to his health by watching and observing. He also received helpful advice from Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park ranger friends. With preparation and planning, Omori became a skilled and accomplished lava flow and landscape photographer, especially during Kïlauea’s 2018 lower Puna eruption that covered 13.7 square miles and destroyed over 700 homes that began on May 3 and subsided in August.

“The one thing I love about it, that I cannot get enough of, is seeing the lava move and how it creates different shapes and forms. The colors, and the smells; it’s never boring. It’s just so unique.”

“I flew on helicopter charters almost every day of the eruption. This is one of the primal forces of the planet and cannot be taken lightly,” said Omori seriously about his passion.

“The one thing I love about it, that I cannot get enough of, is seeing the lava move and how it creates different shapes and forms. The colors, and the smells; it’s never boring. It’s just so unique,” shares Omori with excitement. “Volcanic activity is very dynamic; it’s always in a constant state of change. I’ve never seen or experienced anything like it. It’s just so fascinating. For a photographer, that’s really unique. You could say the same thing about other things, like the weather I suppose. But the amount of change is just amazing. It’s just mind blowing to me. It can be so destructive, as well as beautiful. It destroys, yet it creates,” said Omori with wonder.