‘Sparking that musical appreciation:’

Family traditions bring community together through music

By elise takahama

Lisa Joe was a natural musician from a young age. It wasn’t just her talent, her mother once said. It was her drive. Even when Joe was a child, she practiced the flute so much it drove her mom, an acclaimed music teacher, crazy.

The Long Beach native started playing when she was 9, spending two to four hours a day repeating exercises and arrangements. By the time she got to high school, she was practicing three to six hours a day. “That’s just what I wanted,” she said in a recent interview.

“I think practice is an art, and that’s something my mother taught me. Technique is a skill, and it’s through repetition.”

Despite her mother’s occasional exasperation, practice and repetition were core principles in her teaching methods for years, Joe said. And more than 50 years later, Joe has learned to share and embrace her mother’s life passion of teaching music — particularly to elevate Japanese American stories and bring community together through organizations and groups like East West Players and the Grateful Crane Ensemble, as well as her lively Orange County “Happy Hour Chorale.”

“I kind of equally enjoy playing and performing, but there is nothing like sparking that musical appreciation in another person,” Joe said.

Soji Kashiwaji, Grateful Crane’s founder and Joe’s longtime friend and collaborator, said he’s consistently stunned by Joe’s dedication and talent to musical theater. Grateful Crane is a long-time LA- based traveling theater company that pays tribute to Japanese American history.

“Having been a musician for most of her life, Lisa really knows music and as a music teacher and vocal coach, she is able to bring all of her knowledge and experience to every student she teaches,” Kashiwaji said.

“She is passionate about what she does, and works hard to make sure it is done right.”

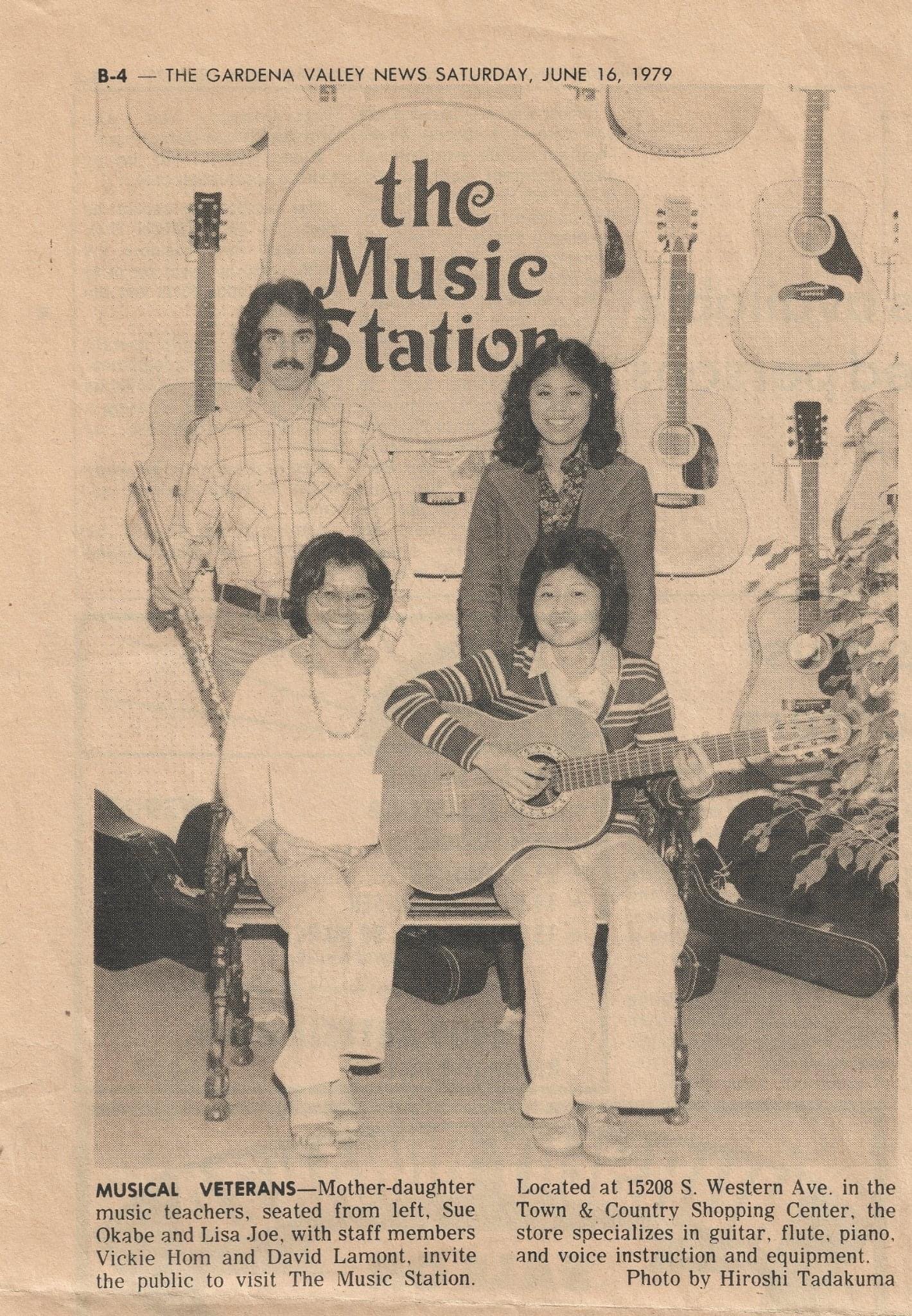

Lisa with her mother, Sue Okabe

Joe was born in 1956 and has spent most of her life performing and teaching in the South Bay. She first started helping her mother, Sue Takimoto Okabe, teach music when she was 13 years old, and eventually started working more regularly in their Gardena music store and school in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“Music was always a part of our family,” she said. “But even still, my mother always discouraged us from making it a vocation. She knew how difficult of a lifestyle it was. It was something to fall back on. But I eventually realized I was kind of just fighting myself [in avoiding music professionally] and had not been completely happy my whole adult life because of that.”

After Okabe sold the music shop in 1984, Joe decided to quit her side jobs, like working at her brother’s kite shop on the Redondo Beach pier, and commit full-time to performing music professionally.

“I wanted to keep myself hungry to take whatever music job,” she said. “To only make a living by making music.”

It was a big leap, she said, but she eventually joined East West Players, a Little Tokyo-based performing arts company known for its Asian American productions. There, she was musically involved with everything from “Little Shop of Horrors” to “Into the Woods” — mostly from EWP’s old, 99-seat theater with no microphones.

She and Scott Nagatani, EWP’s former musical director, quickly became a well-known duo in LA’s Japanese American community, spending hours studying the conductor’s score and learning to play entire orchestral performances with just two people.

“I would be the woodwinds and brass section,” she said. “Scott knew how to blend everything else. Piano, bass, strings. We got good at knowing how to make that sound not fake, yet still full enough so that the intimate production could be done. That was the challenge.”

She spent years taking whatever freelance gigs she could get — at the LA Children’s Museum, West Covina Valley Playhouse and Brentwood Theater Company, among others.

“I’d have three or four theater [productions] going on at a time,” she said. “My life was so immersed into whatever show I was working on. Then maybe I might not have a job for a few months. Then there’s another one. … It was hard when you don’t have a safety net like a ‘regular job’ and there were some tough financial times, but for the most part — I don’t know whether it was luck or meant to be — I’ve always managed to cover my expenses.”

In spring 2002, Okabe was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, bringing a sudden halt to Joe’s whirlwind performance schedule.

Her mother died about six months later in November 2002.

Lisa with Brother & Dad

When the 20th anniversary of Okabe’s death passed last fall, Joe said she realized she’s often reminded of her mother’s influence.

“Outside of teaching, my mother was someone young people always seemed to go to when they needed advice,” she said. “And that’s what I got from her. It was more about making sure you’re helping.”

Okabe also began music as a child, picking up singing when she was 6 or 7 years old and living in Seattle. She often performed at the local Buddhist church, and once at the Japanese American Citizens League’s national convention.

When Okabe (nee Takimoto) and her family were incarcerated in Minidoka during World War II, she became known as such a good singer that camp administrators instructed soldiers to take her to other Idaho cities to perform.

“For the most part, they were pretty nice,” Okabe said in a 1999 Densho interview about her time in camp. “Twin Falls was nice. Blackfoot was nice. Idaho Falls, too. But Boise was kind of far, and I had trouble there where people would yell, ‘What’s the Jap doing here?’”

But she was a perfectionist and a trained performer.

“In performing, you learn two things: There’s no room for vanity if you’re going to perform, and have no expectations from the audience,” Okabe said. “I learned early that you can ignore it. It hurts, but you don’t show it.”

In recent years, individual gigs and musical performances have taken a backseat to teaching and community engagement, Joe said.

She spent about a decade organizing and directing what became known as the “Happy Hour Chorale,” a singing group made up of her friends and students in Orange County. The group became close friends — and always made time for happy hour food and drinks after rehearsal.

Ladies of the Happy Hour Chorale

In 2016, she traveled to Tohoku with the Grateful Crane team for its annual goodwill tour, following the city’s devastating earthquake and tsunami. And this year, even though big musical performances take a lot of time and effort, she has plans to take on more responsibility and return as the ensemble’s musical director.

“It wouldn’t matter what I did, if it was kites or music,” she said. “It’s all about meeting people. This is how you find your tribe.”

Lisa with Nephews & Nieces